Binary Exploitation 101 - FSA and GOT Overwrite

This blog series is still a work in progress. The content may change without notice.

In this chapter, we’ll learn about FSA (Format String Attack) and GOT (Global Offset Table) overwrite, along with their mitigations, RELRO (RELocation Read-Only) and PIE (Position-Independent Executable). The materials for this chapter can be found in the chapter_08 folder.

Introduction

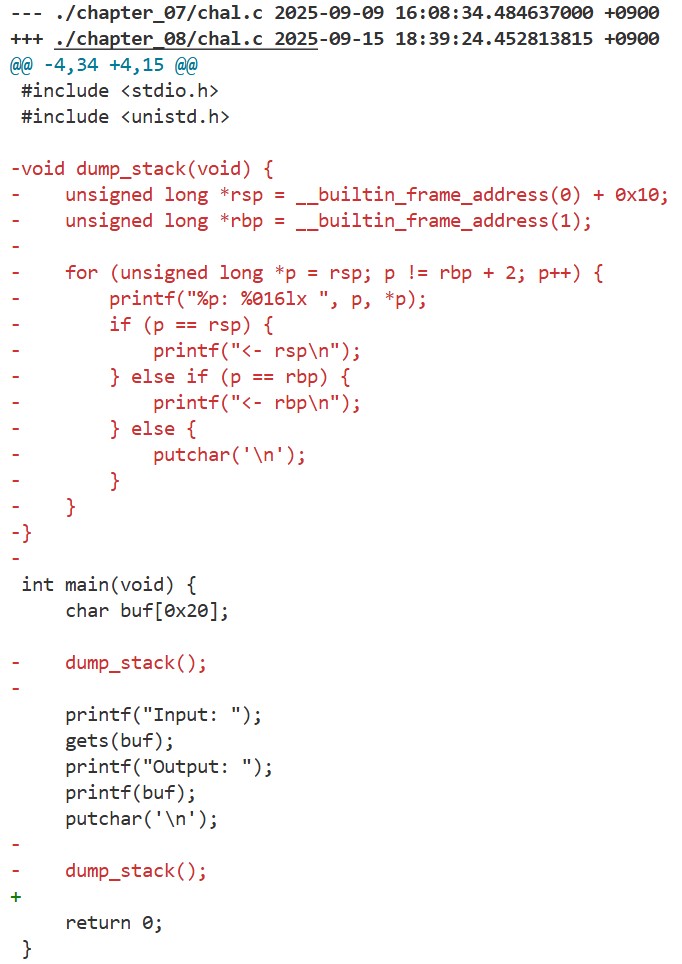

If we look at this chapter’s chal.c, we’ll notice that the dump_stack function has been removed:

So far we’ve leaked the stack canary and the glibc base address from the output of dump_stack, so we can’t reuse our previous exploit as-is. Is it still possible to leak the stack canary and the glibc base address in this situation and spawn a shell? To answer that, we first need to understand how the printf function works.

How printf works

The printf function takes a variable number of arguments. The 0th argument is the format string, and the 1st and later arguments are the values that match the format. The grammar of a conversion specification is:

1

%[argument$][flags][width][.precision][length modifier]conversion

For example, consider the following program. With %016lx we can print the corresponding argument as a 16-digit hexadecimal number. By using the 0 flag, any missing digits are zero-padded. We can also use %m$ to explicitly select which argument to use. The %n specifier writes the number of bytes printed so far to the corresponding address. By using length modifiers such as h or l we can control how many bytes are written. See the man page for details:

1

2

3

4

5

6

int main(void) {

int n = 0;

printf("%016lx\n", 0x1l);

printf("%2$016lx%1$016lx%3$n\n", 0x1l, 0x2l, &n);

printf("n = %#x\n", n);

}

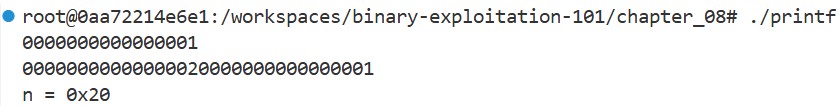

When we run this program, we get the following result:

The printf function looks up the corresponding arguments according to the format string. However, this behavior depends on the assumption that each conversion specification has a matching argument.

Now look at the following part of chal.c. Here printf is called with only a single argument. If we place a conversion specification into that argument, the corresponding arguments for the conversion specifier are not actually passed — thereby breaking the assumption above. Can we do something interesting with this?

1

printf(buf)

FSA

As explained in the Buffer Overflow chapter, under the System V ABI, function arguments are passed in the registers rdi, rsi, rdx, rcx, r8, and r9 in order, and any additional arguments are passed on the stack.

Now, we can freely control the format string passed to printf, and by using %m$, we can explicitly select which argument to access. By using this cleverly, we can leak the stack canary and the libc base just like before.

Let’s examine the “arguments” of the printf function in GDB. We can start GDB, set a breakpoint at printf(buf), and run the program using the following command:

1

pwndbg -q --ex 'b *0x4011c2' --ex 'r' ./chal_patched

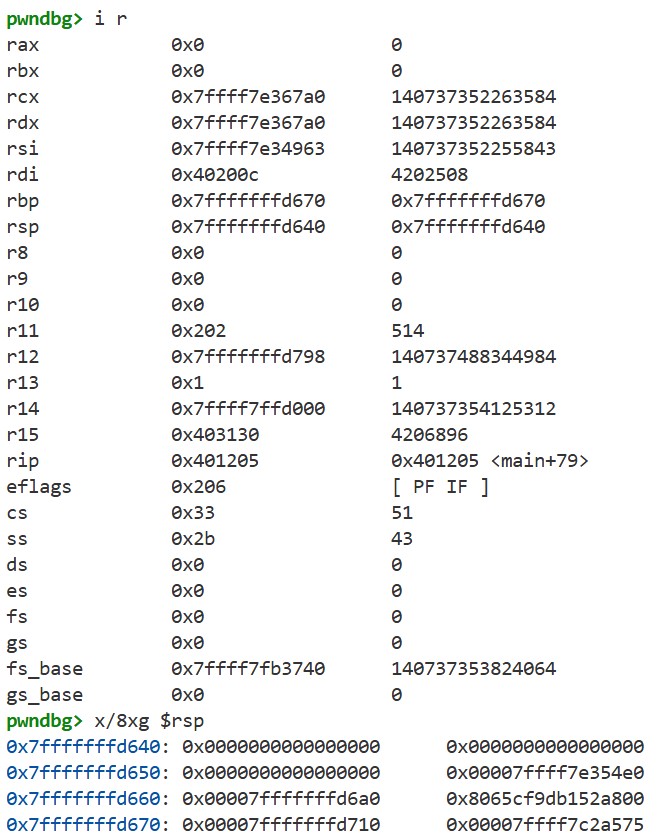

Using i r and x/8xg $rsp to see the registers and the stack frame, we get the following:

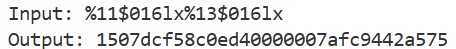

The stack frame contains the stack canary and the return address of the main function. From printf’s perspective, these correspond to the 11th and 13th “arguments”. In fact, if we provide the following input, we can leak these values just like before. Even though the program does not actually pass these arguments, printf accesses them according to the conversion specifications and the System V ABI:

1

%11$016lx%13$016lx

Recall that the buf variable is located at the position pointed to by the rsp register. Using gets(buf), we can write arbitrary values here, and with %m$, we can explicitly specify which argument to access. In other words, we can make the printf function read the values we write into buf.

What happens if we combine this with %n? The %n specifier writes the number of bytes printed so far to the corresponding address. The number of bytes printf outputs can be controlled to some extent using the field width. By combining these techniques, we can write arbitrary values to arbitrary memory locations. A small bug like printf(buf) gives us a powerful primitive for arbitrary read/write. This technique is called a FSA (Format String Attack).

Now, with FSA, we have obtained an arbitrary read/write primitive. The remaining question is how to use this to spawn a shell. As explained in the FSA section, we can leak the stack canary and the libc base address, so we can still construct a ROP chain as before. If we can somehow transfer control to the ROP chain, we can spawn a shell. However, the previous method of overwriting the return address of the main function is difficult, because the stack canary and libc base address are only known after the printf(buf) call — we cannot know these values when crafting the payload.

Still, we are very close. If we could execute the main function again after printf(buf), we could use a ROP chain as before to spawn a shell. Is this even possible? In fact, it is. But to achieve this, we first need to understand how calls to shared library functions work.

GOT and PLT

As explained in the Buffer Overflow chapter, functions are called using the call instruction. The operand of a call specifies the function’s address, but as discussed in the ASLR chapter, when ASLR is enabled, the base address of glibc changes on each execution. In other words, the addresses of functions in glibc cannot be known at link time.

However, in chal.c, we are using glibc functions like printf and putchar. How is this possible?

Let’s trace the behavior in GDB. We can start GDB, set a breakpoint at the call to putchar, and run the program using the following command:

1

pwndbg -q --ex 'b *0x4011cc' --ex 'r' ./chal_patched

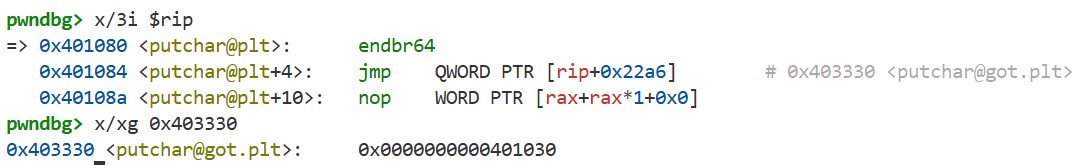

By executing si and then using x/i $rip, we get the following:

We can see that the code in the .plt section is being executed, not the putchar function itself. Here, it jumps to the address stored at 0x403310. From the previous output, we can see that its initial value is 0x401036.

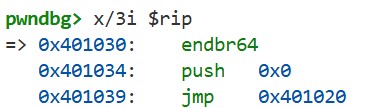

Execute si to step into the code at 0x401036. Displaying the instructions with x/2i $rip gives the following:

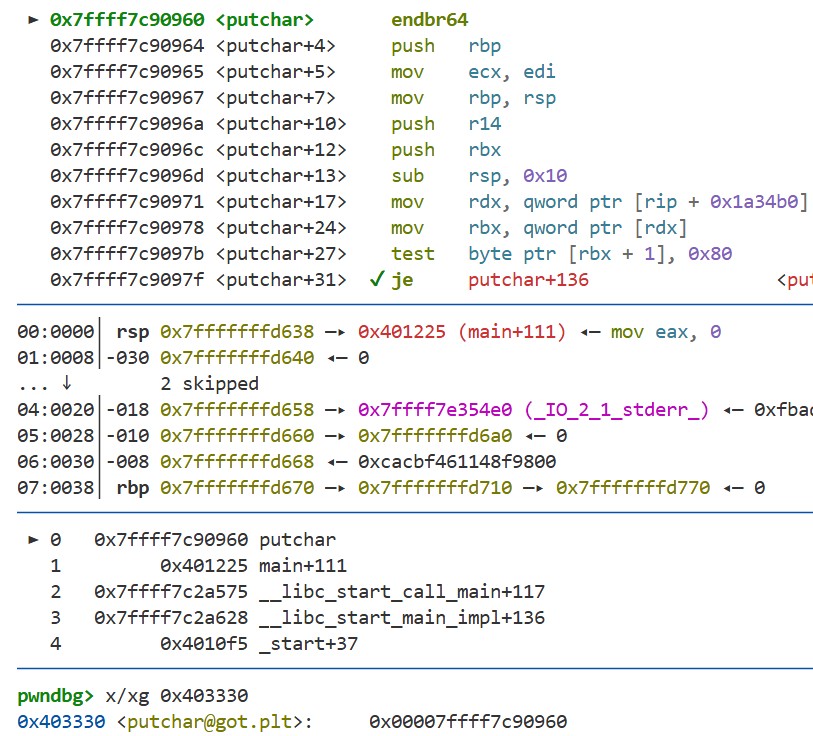

Here, 0 is pushed onto the stack, and a jump is made to 0x401020. As we will see in the next chapter, these instructions call the dynamic linker to resolve the address of the putchar function. In fact, if we set a breakpoint at putchar using b putchar and continue execution with c, we can see that the putchar function is executed. Running x/xg 0x403310 again shows that this address now contains the actual address of the putchar function:

Recall that in the .plt section code, the jump goes to the address stored at 0x403310. As a result, when putchar is called the next time, the dynamic linker is not invoked, and execution jumps directly to the putchar function’s code.

In summary, calls to shared library functions are implemented using the PLT (Procedure Linkage Table) and the GOT (Global Offset Table). By using the PLT and GOT, whose addresses are known at link time, and having the dynamic linker resolve the actual function addresses, we can call shared library functions even when ASLR is enabled.

GOT Overwrite

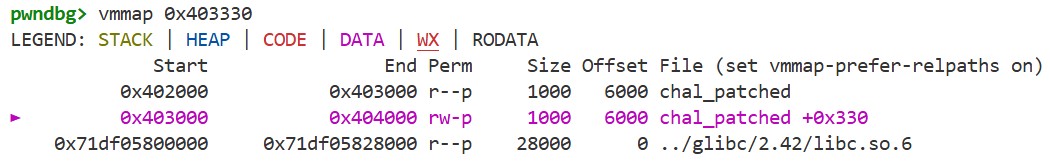

if we run vmmap 0x403310 in GDB, we can see that the .got.plt section resides in a writable segment:

Moreover, this address does not change even when ASLR is enabled (if PIE is disabled). Now, with the arbitrary write primitive obtained via FSA, we can overwrite 0x403310. This allows us to redirect execution to any location when putchar is called. The address of the main function also does not change (if PIE is disabled), so we can use this to execute main again after printf(buf).

Exercise

Based on what you have learned so far, write an exploit using FSA and GOT overwrite, and launches a shell. Before you start, make sure to execute the following command to enable ASLR (if you are using a Docker container, run it on the host):

1

sudo sysctl -w kernel.randomize_va_space=2

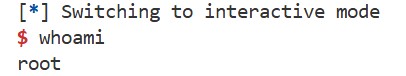

You can use the template, and the following hints may help. If successful, you should be able to launch a shell like this:

If you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below. You can see my solution here.

If you have time, consider whether the attack would still work even if the putchar function were removed. (Hint: as explained in the SSP chapter, if the stack canary value differs from its original value, the __stack_chk_fail function is called. This function is also part of glibc, so it is invoked using the PLT and GOT in the same way as the putchar function.)

Hints

- On x86-64, only 8-byte aligned push/pop is possible, so the arguments specified to

printfmust be placed at 8-byte aligned addresses. - The initial value at 0x403310 is 0x401036. Since the address of the

mainfunction is 0x401166, you only need to overwrite the lower 2 bytes. Using%hnis recommended. - To control the number of bytes printed, you can use

%ctogether with the field width.

Mitigations

How can we prevent the attack described above? It relies on the .got.plt section being placed in a writable segment and on the fact that the addresses of this segment and the main function do not change even when ASLR is enabled. To mitigate this, we can make the .got.plt section read-only and randomize the base address of the binary on each execution. The mitigations that provide these protections are RELRO and PIE, respectively.

RELRO

RELRO (RELocation Read-Only) is a security mechanism that makes the segment containing the .got.plt section read-only. In the previous chapters, we disabled this by specifying the -z norelro option at compile time. To enable it, we can pass -z relro -z now to gcc. When RELRO is enabled, the addresses of all glibc functions are resolved at load time, and the segment containing the .got.plt section becomes read-only, preventing GOT overwrite attacks.

PIE

PIE (Position-Independent Executable) is a security mechanism that makes the executable code position-independent, allowing the binary’s base address to be randomized on each execution. In the previous chapters, we disabled this by specifying the -no-pie option at compile time.

Position-independent means that the code can run correctly regardless of the address it is loaded at. Since absolute addresses cannot be used in position-independent code, PC-relative addressing is employed. As a result, the addresses of the main function and the segment containing the .got.plt section are randomized on each execution, making GOT overwrite attacks difficult. However, just like ASLR, if there is a way to leak the base address, the protection can be bypassed.

If you have time, you can try testing whether the attack still works when PIE is enabled but RELRO is disabled. If it does not work, consider under what circumstances it could still be possible.