Binary Exploitation 101 - Shellcode

This blog series is still a work in progress. The content may change without notice.

In this chapter, we’ll learn how system calls work and shellcode. The materials for this chapter can be found in the chapter_04 folder.

Introduction

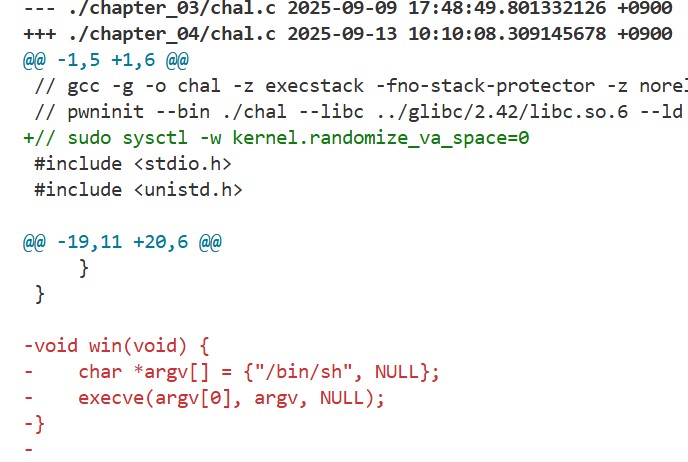

If we open chal.c, we’ll see the win function has been removed. Everything else is unchanged. As in the previous chapter, we can still take control via buffer overflow, but the real question is how to spawn a shell. To answer that, we need to analyze what the win function did and understand how system calls work.

How System Calls Work

A system call is the mechanism that lets user-space programs use services provided by the OS kernel. The win function spawned a shell by invoking the execve system call. Now let’s study how system calls work using win.c as an example. The program is exactly the same as the win function from the previous chapter:

1

2

3

4

int main(void) {

char *argv[] = {"/bin/sh", NULL};

execve(argv[0], argv, NULL);

}

Start pwndbg with the following command:

1

pwndbg -q --ex 'b main' --ex 'r' ./win

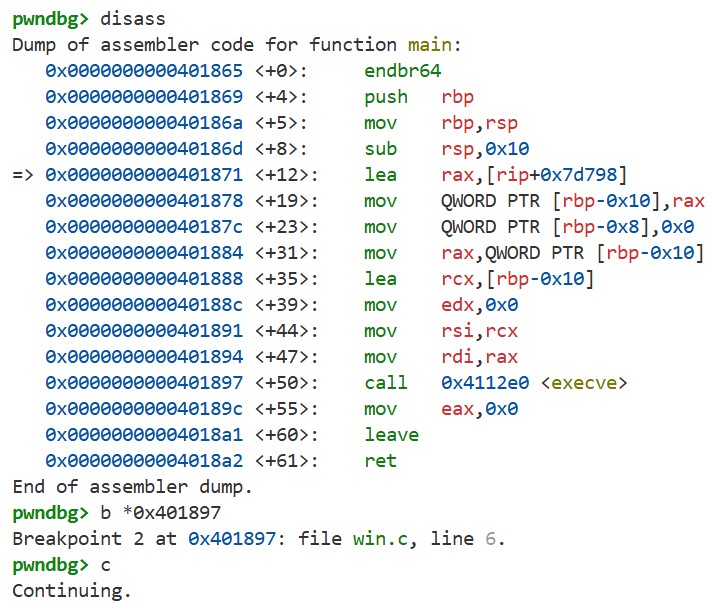

Use disass to see main in assembly, set a breakpoint at the execve call with b *0x401813, and continue with c:

execve takes three arguments. As we learned earlier, under the System V AMD64 ABI the first three arguments are passed in rdi, rsi, and rdx. You can confirm this with i r rdi rsi rdx, x/s $rdi, and x/2xw $rsi:

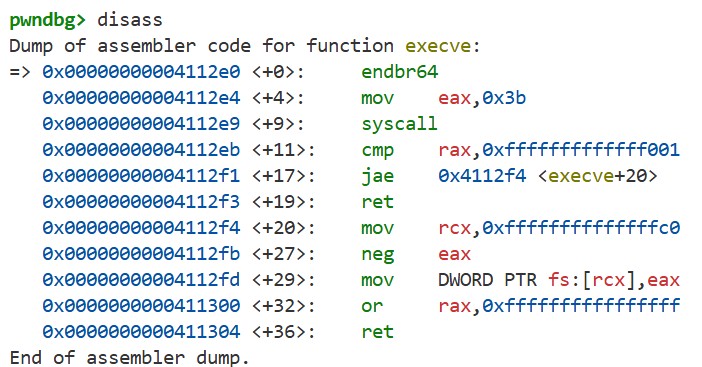

Next, step into the execve function with si, then use disass to see the assembly:

Here the code places 0x3b in eax and executes the syscall instruction. The syscall instruction transfers control to the kernel’s system call handler. Under the System V ABI, the system call number is placed in rax and the syscall arguments are placed in rdi, rsi, rdx, r10, r8, and r9 before executing syscall. See the spec section “A.2.1 Calling Conventions” for details.

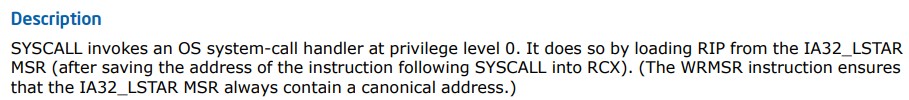

One important difference from ordinary function calls is that the fourth argument (0-indexed) is passed in r10 rather than rcx. This is because the syscall instruction uses rcx to store the return address. For more details, see the Intel SDM:

Shellcode

Now that we have learned how to invoke system calls in assembly, let’s actually write shellcode that executes a shell:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

.intel_syntax noprefix

.global _start

_start:

xor rdx, rdx

push rdx

mov rax, 0x68732f6e69622f

push rax

mov rdi, rsp

push rdx

push rdi

mov rsi, rsp

mov rax, 0x3b

syscall

Here, 0x68732f6e69622f is the hexadecimal representation of “/bin/sh”. We set rdx to NULL, push “/bin/sh” onto the stack, and store its address in rdi. Then we push rdi and NULL onto the stack to construct argv, and store its address in rsi. Finally, we set rax to the execve system call number (0x3b) and execute the syscall instruction. You can step through this in GDB to see the details. Running this program confirms that the shell launches as expected.

Exercise

Based on what you have learned so far, write an exploit that launches a shell using shellcode. Before you start, make sure to execute the following command (if you are using a Docker container, run it on the host):

1

sudo sysctl -w kernel.randomize_va_space=0

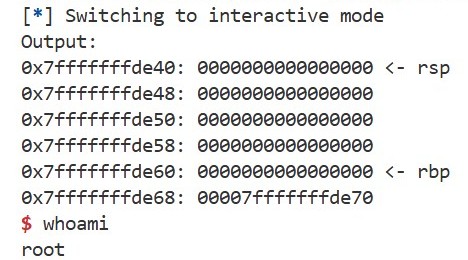

This command disables ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization), which will be explained in a later chapter. You can use the template, and the following hints may help. If successful, you should be able to launch a shell like this:

If you have any questions, feel free to leave a comment below. You can see my solution here.

Hints

- The size of

bufis 0x20 bytes, which is too small to hold the shellcode. It is better to place the shellcode after the return address. - Even with ASLR disabled, the stack address may differ depending on whether you run the program in a debugger, normally, or via a Python script.